Like all connoisseurs in imperial China, the 17th-century playwright Li Yu took very seriously the art of displaying fine pieces: “Displaying objects in the correct way is as essential as promoting talented people to a high position” [1]. He recorded his views on every aspect of elegant living, ranging from architecture to the arrangement of items on the desk. Some of his views are baroque and may have been controversial at the time. He had a taste for opulent visual effects such as irregular polygons of wallpaper patched together to imitate the surface of cracked porcelain. Such inventions would probably have been termed su (vulgar) Wen Zhenheng, gentleman scholar and author of the Treaty of superfluous things [2]. But all agreed that providing a worthy environment for treasured objects was an important part of a collector’s activity. In particular, finding a display stand was a way to participate in the creation of the work of art, considered as a continuous process that could span several centuries, and imply the collector as well as the artist.

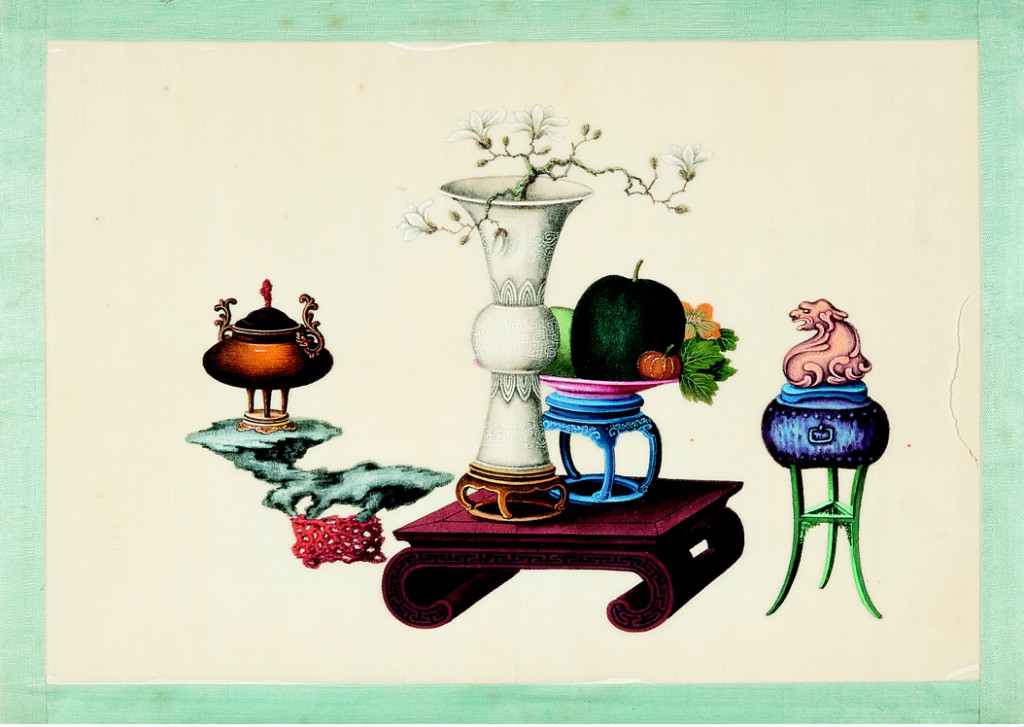

The Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723-1735) commissioned the famous set of painted scrolls known as Guwan tu (Playful things) to serve as a visual catalogue of imperial collections. Several of the scrolls are still extant, and hardly any piece is depicted without a stand. Some antique bronze vessels are fitted with wooden stands (and covers) of more recent manufacture. Indeed regular commissions of stands are recorded in the imperial archives. Genre paintings, illustrations of novels and depictions of the hundred antiques confirm the extensive use of display stands in the classical Chinese living environment, not necessarily in an imperial context.

Display stands as a brief history of Chinese furniture and taste

Beauty and practicality were combined in stands. They provided stability to meiping vases and rocks of elaborate forms, some of which defy gravity. Even though the stand was not meant to distract the viewer from the contemplation of the object, it could complement it by a continuity of style, or by deliberate contrast between materials (through the association of a hardwood stand to a bamboo object, for instance).

The best display stands share all the characteristics of antique Chinese furniture. The craftsmanship obeys the same rules: it is based on mortise-and-tenon joinery, with minimal use of glue, if any. Wooden stands can therefore serve as witnesses of the artistic evolution of Chinese furniture.

The materials are just as refined in stands as in full-scale pieces of furniture. The rarest tropical hardwoods, such as huanghuali, come from slowly-growing trees. The small scale of stands makes them natural candidates for the use of finely-grained but small pieces of wood. When tropical woods started to be imported in large quantities in China in the late Ming dynasty, the taste of the literati was dominated by the purity of simple geometric shapes. The patterns of the highly-figured grain of huanghuali was termed ke ai gui mian (adorable demon faces) by Ming scholars. In some Ming-style stands, the grain of the wood is the only ornament of the piece, which lends them a surrealist quality. Their appeal therefore reaches far beyond the culture in which they were produced. On the other hand, stands made during the Qianlong era of the Qing dynasty (1736-1796) combine dramatic effects such as asymmetry and contrast between essences of wood, to ornaments that range from archaic patterns inspired by antique bronzes and jades to symbols treated realistically.

Moreover, the distinction between furniture and stands is ultimately conventional. The two categories are almost merged by the existence of miniature tables, which can be considered as self-sufficient works of art, or as stands. There is a continuum of scales between the corner-legged stands and the smallest kang tables.

Another border-line case between stands and furniture is the duobaoge, or multiple-treasure shelf, a type of shelf with irregular compartments, each fitted to display one object. The smallest extant duobaoge function well as table-top cabinets, and almost fit into the category of scholar’s object. On the other hand, a duobaoge can take the proportions of a floor-to-ceiling display shelf. Examples of architectural proportions can still be seen in the Palace Museum in Beijing [ 3 ], and are described with minute precision in Dream of the Red Chamber, the well-known 18th-century novel by Cao Xueqin.

Displaying collections, collecting display stands

The interest for display stands as collector’s items is therefore artistically grounded in the exquisite craftsmanship that matches the quality of the works of arts they were meant to support. It should also be noted that market forces have recently triggered this interest, and will continue to do so. The scholarship on Chinese furniture developed extensively since the American embargo on mainland China was lifted in 1972. The corresponding market went global and commanded increasingly high prices. Since the Wang Shixiang collection was exposed in the Shanghai Museum, it has become increasingly difficult for the private collector to acquire genuine pieces of classical Chinese furniture, even though the amount of knowledge available from the literature and from museums enables connoisseurs to develop and refine their taste.

As a result, the attention of demanding collectors has been attracted to smaller pieces that retain all the features of classical Chinese furniture, even though they have been separated from the objects they once supported. Chinese wooden stands have now developed as an autonomous collecting field, with outstanding published collections documenting Ming and Qing stands in a variety of woods [ 4 ].

Contemporary collectors can speculate, as an educated guess, about the nature of the object for which some one-of-a-kind stands were made. One can even pursue the archeological dream of reuniting a stand to a matching object, thereby continuing the Chinese tradition of involving the beholder in the life of a work of art.

References

[ 1 ] J. Dars, Les carnet secrets de Li Yu, un art du bonheur en Chine (2009), Éditions Philippe Picquier. [ 2 ] Craig Clunas, Superfluous Things, Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. University of Hawaii Press (2004). [ 3 ] Forbidden City Publishing House, Interior design in the Forbidden City. [ 4 ] P. Mak, The Art of Chinese Wooden Stands, the Songde Tang collection, University Museum and Art Gallery, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.如古代中國許多鑒藏家一样,明末清初的著名文學家以及劇作家李漁對於陳列器玩秉持着一种非常審慎的態度:“位置器玩与位置人才同一理也。設官授職者,期于人地相宜;安器置物者,務在縱横得當。”

李渔的這一觀點在其生活美學的所有方面都有所體現,包括對於家居的擺放以及案頭器物的陳列。縱然他的一些言論在當時標怪立異,譬如他將剪裁下来不規則的多邊形的壁紙拼凑成冰裂纹置于墙上以追求繁復華美的視覺效果,這一類發明可能被當時的文人,例如著有《長物志》的文人雅士文震亨稱之為俗。

但是,將珍貴的器玩妥善陳列并置于適這一重要的收藏傳统為人所共識。尤其是收藏家為器玩尋永契合的陳列座子以提升其觀賞價值這一行為本身就是融入了藝術的再創造之中,將藝術創造這一過程延續至幾個世纪之後,收藏家同時也在其中轉變為藝術家的角色。

雍正帝(1723-1735)曾下旨繪製一组《古玩圖》,以圖錄的形式纪錄宫廷收藏,如今仍有少幅存世,画中幾乎所有繪制的珍貴物件都配有合適的座子陳列。一些古铜器配有後世量身定做的木座(以及木蓋)。同樣,在用以描繪傳統中國古代生活場景的風俗畫中,可以看到上百例用以陳列器玩的座子,可以想見座子在當時被廣泛使用,並不僅限於宫廷之内。

中國傳统家具及審美趣味的完美折射

每一個陳列座子都兼具美與實用性。他们以自身為置放梅瓶或山子擺件提供足够的稳定,甚至有一些巧夺天工的座子能够挑戰重力。縱使座子的目的並不旨在吸引觀賞者對於擺件的注意力,然而它通過與擺件形式上的呼應或者為擺件材質上微妙的反差,恰恰能突出陳列於其上的摆擺件的觀賞效果来吸引觀賞者的注意(例如硬木座子與竹雕擺件的組合)。

最佳的陳列座子具有中國古代家具的一切優秀品質。它们的工藝遵從相同傳統與法式:完全基于木榫結構并最少量的使用粘合劑。木質座子因此也見証着中國家具藝術轉變的進程。

木雕座子所使用的材料也与大尺寸的家具同樣珍貴,例如生長十分缓慢的珍稀热帶硬木黄花梨。而小尺寸的座子使一些虽然體積不大卻木纹優美的木料自然而然地成為最佳候選。

晚明時期,熱帶木料大量進口國内,屆時文人對於木雕的品味更注重纯正簡約的天然幾何紋飾,例如黄花梨上形似人物的木紋即被明代文人稱為“可爱鬼面”。在一些明式木座中,天然的木纹是僅有的裝飾,這同樣賦予明式座子一絲超現實主義的氣息。因此它们的吸引力超脱于當時所處的文化直到現在。而另一方面,清乾隆时期(1736-1796)所製作的木座將一些戲劇化的效果例如不對稱以及木材之間的對比组合融入木座的裝飾中,並借鑒古铜器與古玉器上的纹飾進行仿古圖案的設計。

並且,家具與木座之間的區别最终只是基於習惯上。由于小型幾座這樣介於藝術品與木座之間的存在,這兩種品類幾乎没有分别,从小的方形木座到大的炕案可以找出一个木座與家具之间完整的連續性。。

另一个介于兩者之間的例子是多寶閣,多寶閣是一種具有多個不規則格子的陳列架,每一個格子對應一種器玩擺件。現存最小的多寶閣與陳列柜一樣,適合文房用具的陳列。另一方面,多寶閣能成為分割人2地面到房頂空間的陳列架,至今在北京故宫博物院仍能看到這一建築式樣,而其裝飾的圖案則是18世纪曹雪芹著名的小说——《红樓夢》。

價值不菲的藏品展示佳物

因此,收藏對於陳列木座的興趣在于其能與座上陳列器玩所媲美的精美工藝,值得注意的是,近来市場的推動也同樣觸發了收藏木座的熱潮,并會延續下去。

自從1972年美國對中國大陸的貿易禁運令取消之后,對於中國家具的研究也快速發展起来。相應的家具市場也走向全球化,價格也不斷走高。

王世襄的红木家具收藏曾在上海博物館展覽,而繼他之后,即使收藏家能够從文獻以及博物馆中能得到相關的知識並提升自身對於傳統家具的品味,對於個人收藏者来說,已经越發困難去尋找和購買像中國傳統家具這樣大件而又精美的藏品。

因此,一些高要求的收藏者被這些秉承了中國傳統家具所有品質的木座所吸引,即使它们離開了那些所要陳列的器件。中國木座本身現在已經發展成了一个獨有的收藏領域,這在那些特别展覽中所陳列的以不同材質製成的明清木座得到體現。

當代的收藏者可以推測南派原件的木座是如何製成的,同樣,也可以推論北派多组構件的製作工艺,因此延續着賞心悦目的中國傳統的木座工藝。